What is it?

Any major change in context—like opening a new window, switching pages, or updating content—must happen only when the user asks for it or when it's expected. That means no surprise redirects, pop-ups, or form submissions unless the user takes action to trigger those changes or it's a predictable behavior.

This success criterion makes sure users stay in control of their experience and aren’t thrown off by unexpected changes.

Comparing WCAG 3.2.1 On Focus & WCAG 3.2.2 On Input

WCAG 3.2.1 On Focus (Level A) prevents context changes from happening just because an element receives focus, like when a user tabs through a form. WCAG 3.2.2 On Input (Level A) takes a similar but slightly broader approach by ensuring that changing the value of a form element doesn’t trigger a context change without an extra user action.

WCAG 3.2.5 goes a step further by requiring that any change of context only happen when users initiate it or can disable it.

Why does it matter?

Unexpected changes, such as a page suddenly refreshing, a form auto-submitting, or a new window opening without warning, can be disorienting, especially for people who depend on consistent, predictable interactions.

When users aren’t expecting a change and don’t have a way to control it, it’s easy to get lost. Giving people the option to trigger changes themselves helps to make the experience feel stable and manageable.

Who is affected?

People with mobility impairments may face challenges with accidentally triggering changes they didn’t mean to, especially if the interface is sensitive or automatically reacts to inputs without a clear confirmation step.

People with low vision or who are blind may not notice when a page refreshes, a form submits, or a new window opens. For example, screen reader users often navigate by headings or landmarks. If content changes unexpectedly, they may lose their place and not realize what's different or how to get back.

People with cognitive disabilities may struggle to understand or keep up with sudden shifts in layout, content, or context. Unexpected changes can interrupt their focus and make it harder to complete tasks or follow through on a process.

How to implement 3.2.5

About This Section

This section offers a simplified explanation and examples to help you get started. For complete guidance, always refer to the official WCAG documentation.

Before diving into how to meet 3.2.5, it’s important to note one subtle exception: if a change in context is clearly triggered by the user and is expected, like redirecting to a thank-you page after a checkout form submission, it’s not considered a violation. The goal is to avoid unexpected or automatic changes, not to block intentional, predictable ones.

Let Users Choose When Changes Happen

No changes of context should happen automatically without the user requesting them or fully expecting them, including:

- Redirects to a new page

- Changing parts of the interface

- Submitting after making a selection

Instead, provide a clear button or link that users can click when they’re ready for the change to happen.

For example, if someone picks an item from a dropdown, don’t auto-submit the form; let them choose an option and then confirm with a submit button.

Even in single-page applications (SPAs), where content updates dynamically without changing the page URL, it's still important to avoid triggering those updates automatically. If the interface shifts or replaces major content areas without a clear user action, it can be just as disorienting as a full page reload. Users should always be in control of when and how those updates occur.

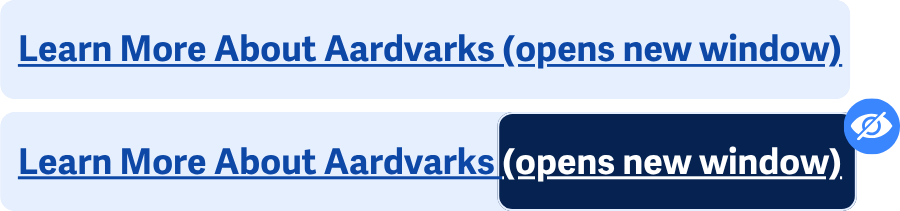

Warn Users Before Opening a New Window

If a link opens a new tab or window, make that clear in the link text. This helps users know what to expect, especially people using screen readers (who don't have visual cues) or screen magnifiers (who may miss new content outside their visible area). For example:

Learn More About Aardvarks (opens in new window)

However, in general, it's best to avoid opening new windows or tabs unless it’s really necessary, since unexpected changes like that can confuse users or make it harder for them to navigate back.

Screen-Reader Only Text

Or, for a cleaner approach that's still screen reader-friendly, use a combination of <span> and CSS to make it clear that the link opens in a new window:

<a href="https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aardvark" target="_blank" rel="noopener">

Learn More About Aardvarks <span class="sr-only">(opens in new window)</span>

</a>

Where the <span> contains the screen reader-only text, and then CSS is used to hide the (opens in new window) text:

.sr-only {

position: absolute;

width: 1px;

height: 1px;

padding: 0;

overflow: hidden;

clip: rect(0 0 0 0);

white-space: nowrap;

border: 0;

}

target attribute

While the target="_blank" attribute opens links in a new window, it doesn't always inform users on its own, especially those using screen readers. Always pair it with visible or screen reader-only text to let users know what to expect.

<a href="https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aardvark" target="_blank">

Learn More About Aardvarks (opens in new window)

</a>

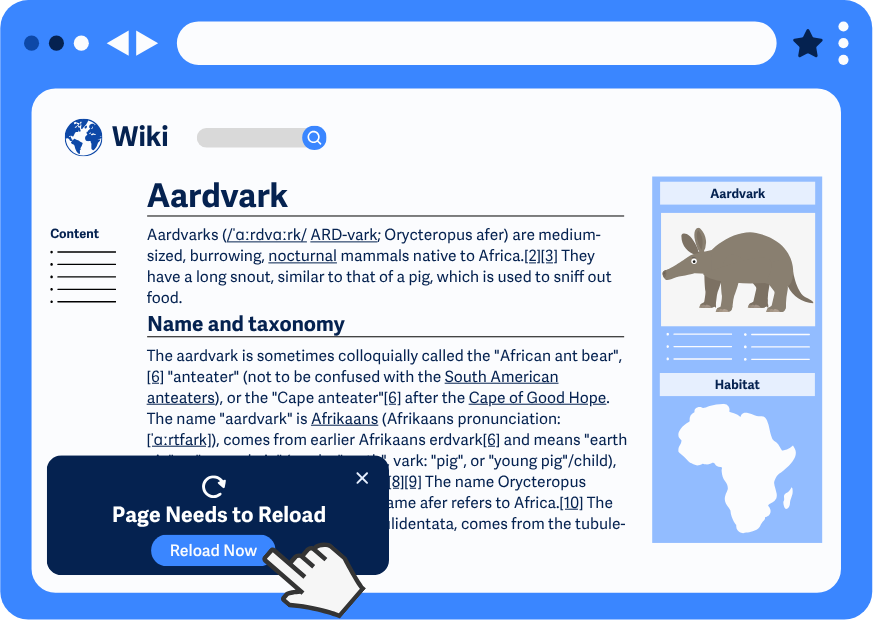

Avoid Surprise Pop-Ups

Pop-ups can easily disrupt a user’s experience, especially if they appear without warning or user interaction. Therefore, pop-ups or modals should only happen when the user initiates them with a button or link, or after an action where it's expected. For example, leaving a page without saving could prompt a modal asking the user if they want to save their changes.

When possible, consider simpler alternatives like inline content or separate pages, which are often more predictable.

Avoid Browser-Based Redirects

If your site needs to redirect users, like sending them from an old domain to a new one, make sure it doesn't happen in the browser session or with any lag. Browser-based redirects like a <meta refresh> tag, can be disorienting for users who are in the middle of reading or interacting with content, and some screen readers may not announce the change clearly.

Instead, handle redirects on the server side so they happen instantly when the user first loads the page. This avoids unexpected shifts and makes sure the back button works as expected.

Exceptions for Change on Request

Some types of content, such as slideshows or auto-advancing carousels, need to change context automatically to work correctly. Those cases are counted as exceptions, as long as they follow WCAG 2.2.2 Pause, Stop, Hide so that users can pause or control the behavior. And the feature follows WCAG 2.3.3 Animation from Interactions, so that their preferences or settings are respected, such as the prefers-reduced-motion CSS property.

Conclusion

Give people the option to click, confirm, or pause before significant shifts happen. When in doubt, ask yourself: “Would this change be confusing if I didn’t expect it?” If yes, it probably needs a user request or a way to turn it off.

If your site or app changes the page, content, or how someone interacts with it, make sure those changes only happen when the user chooses to make them.