What is it?

Links on websites need to be clear and helpful, using their link text alone; they can't rely on the context that surrounds them. That way, screen readers can read the standalone link text and know exactly where it goes, and users can decide if they want to click the link.

The only exception is for links where the purpose is intentionally hidden, like in a game where the mystery is part of the fun. In those cases, unclear link text is okay because it adds to the experience.

2.4.4 Link Purpose (In Context)

WCAG 2.4.4 Link Purpose (In Context) allows link text and its nearby content, such as the enclosing paragraph, heading, list, or table cell, to work together to make the link’s destination clear.

However, WCAG 2.4.9 Link Purpose (Link Only) requires that the link text alone spell out its purpose, so that even in stripped‑down link lists or screen‑reader views, each link still makes sense.

Why does it matter?

When links are unclear, users can feel frustrated because they don't know where the link will take them. This lack of clarity makes it harder for them to decide whether they want to click on the link or not.

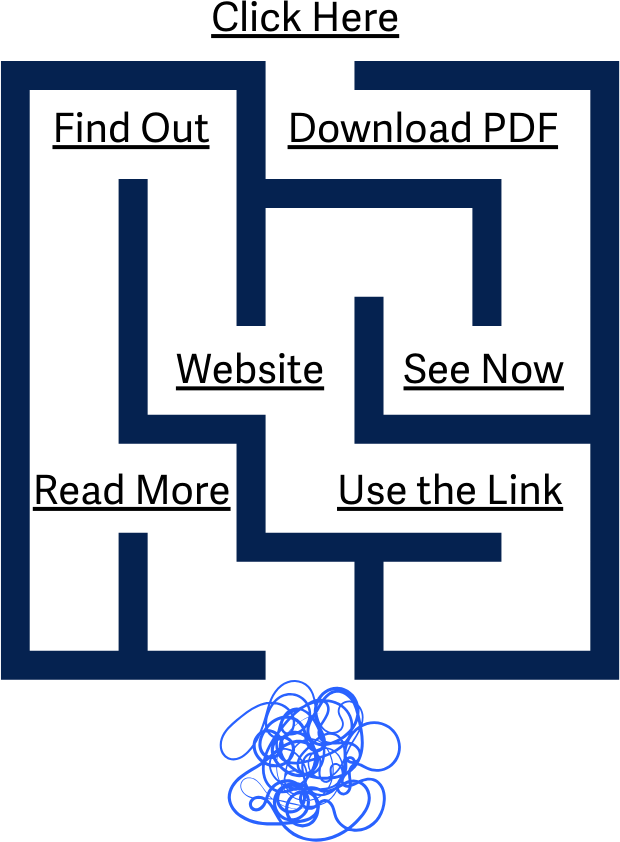

Imagine trying to navigate a website where every link says "click here" or "read more" without any indication of what you'll find on the other side. It's like trying to choose a door without knowing what's behind it.

This uncertainty can make the browsing experience confusing and inefficient, especially for people using assistive technology who rely on clear link descriptions to understand the content of a webpage. Ultimately, unclear links disrupt the flow of navigation and can lead to users feeling discouraged or giving up on exploring the website altogether.

Who is affected?

People with limited mobility can benefit from clear link descriptions by allowing them to skip links that they’re not interested in, saving them from unnecessary keystrokes from visiting irrelevant content. This makes navigation less physically demanding and more efficient.

People with cognitive disabilities may find unclear links and repetitive navigation options confusing. Clear links will make it easier to navigate without becoming disoriented or overwhelmed.

People with low or limited vision who rely on screen readers or other assistive technologies require that links be clear and descriptive. Otherwise, a lot of time is wasted trying to navigate solely based on the context around the links. Screen readers commonly present links in a list to users for navigation around the site, and unclear links make it impossible for the user to know where they need to go or where they’re going.

How to implement 2.4.9

About This Section

This section offers a simplified explanation and examples to help you get started. For complete guidance, always refer to the official WCAG documentation.

Descriptive Link Text

To meet this success criterion, make the <a> element’s link text clearly describe the link’s purpose. The text should be distinguishable from the other links on the webpage and make it clear where the link leads or what it does.

For example, a link could say “Download Aardvark Report (PDF)” instead of just “Download”.

Keep Link Names Consistent

If multiple links go to the same page or have the same function, they must be consistently worded. If they go somewhere different, give each a unique, descriptive name.

Keep Link and Destination Page Names Similar

Keep your link text and the title of the page it points to almost identical. That way, when someone clicks, they land on a page whose heading matches what they chose. It also helps screen‑reader users connect the link they heard with the page they arrive on. For more on page titles, check out WCAG 2.4.2 Page Titled.

Links with Graphics or Images

If the link is solely graphical, for example, the only content within the <a> element is an image, then the alt attribute needs to be included to help describe the link.

<a href="https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aardvark">

<img src="aardvark_animal_icon.png" alt="Aardvark Wikipedia Article">

</a>

However, if you include descriptive text within the <a> element to go alongside your graphic, and any added descriptions would be repetitive, then you can leave the alt attribute empty.

<a href="https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aardvark">

<img src="aardvark_animal_icon.png" alt="">

Aardvark Wikipedia Article

</a>

Switch to Descriptive Link View

For this method, you can add a clearly labeled toggle at the top of your page, for example: View with Descriptive Link Names. And, when clicked, this control could either reload the page or swap link text in place with JavaScript so each link includes the full context needed to stand alone. For example, instead of:

<a href="/report">Download</a>

The page would render:

<a href="/report">Download the 2025 Aardvark Habitat Report (PDF)</a>

You can also save the user’s choice in a cookie or their profile so they only have to switch once. Users who need full link descriptions will always see the descriptive view, while everyone else keeps the shorter, context-based version.

CSS to Hide Descriptive Text

Another approach involves adding descriptive text to a link and using CSS to hide the extra text from being displayed. If done correctly, the text is still accessible to screen readers while allowing the visual design to stay clean.

CSS techniques using visibility: hidden or display: none would hide the text from screen readers. A better approach would be to place the descriptive text in a 1-pixel container with overflow: hidden, so it's not visible on screen but can be read by screen readers.

.visually-hidden {

clip-path: inset(100%);

clip: rect(1px, 1px, 1px, 1px);

height: 1px;

overflow: hidden;

position: absolute;

white-space: nowrap;

width: 1px;

}

And the style can be injected through a <span> contained within the <a> element, like so:

<a href="https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aardvark">Wikipedia

<span class="visually-hidden">Article About Aardvarks</span>

Image Maps

Image Maps are special types of images that include selectable <area> regions within them that count as links. In addition to the <img> overall alt text description, each <area> must also provide its own alt attribute to describe its purpose.

aria-label attribute

It’s worth noting that the best way to handle link purpose accessibility is through the methods listed above; however, if you must use custom interactive elements, ARIA can help ensure your links still have context.

The aria-label attribute adds a text label to a link when there is otherwise no visible text describing it.

In this example, the screen reader will ignore the visible link text ("Continue reading...") and instead announce "Continue reading about Aardvark habitats and food sources." using the aria-label found within the link or <a> element.

<a aria-label="Continue reading about Aardvarks and their habitats and food sources."

href="https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aardvark">

Continue Reading…

</a>

Conclusion

By giving every link its own descriptive name, you empower all users, especially those using assistive devices, to navigate your site confidently and efficiently. Descriptive link writing is a small habit that leads to a big impact, so write with clarity from the start.